The nineteenth century saw an unprecedented migration to cities as industrial employment concentrated populations into urban centers.

This structural shift transformed how people lived, worked, and interacted within dense neighborhoods and emergent public spaces.

Changes in housing, transport, public health, and leisure were all interconnected, producing both opportunities and significant challenges.

Understanding these dynamics helps explain patterns of modernization that continued to influence later eras.

Urban migration and housing

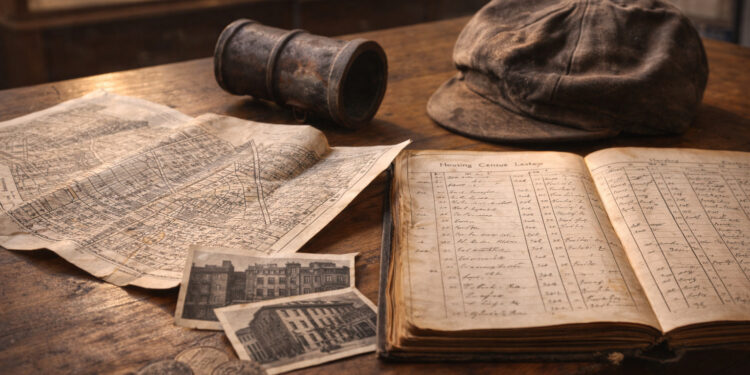

Rapid migration altered housing supply, often outpacing planners and leading to crowded tenements and informal settlements. Many newcomers lived in small, multi-family dwellings where ventilation and privacy were limited, and landlords prioritized occupancy over comfort. Housing often clustered near factories and transport nodes, reinforcing socio-economic divisions. The built environment thus became a visible marker of inequality and a catalyst for social reform movements.

– Overcrowding increased disease transmission.

– Short-term lodging and lodging houses blurred family structures.

Efforts to improve housing ranged from building affordable models to passing regulatory codes, though enforcement varied. Municipal initiatives began to map and regulate living conditions.

Work, industry, and daily routines

Industrial workplaces shaped daily rhythms, imposing set shifts, mechanized tasks, and new gendered divisions of labor. Work moved away from seasonal agrarian patterns to continuous production cycles, altering family schedules and leisure time. For many, wage labor introduced monetary dependence and new consumer habits centered on markets and shops. These shifts affected class identities and stimulated political organizing among workers.

Labor-saving domestic technologies appeared unevenly and did not immediately reduce household workloads for many. Community networks often supplied mutual aid where wages and services lagged.

Public health and infrastructure

Dense urban populations exposed weaknesses in water, waste, and transport systems, prompting public health responses that combined science, engineering, and policy. Municipal governments invested in sewers, piped water, paved streets, and later public transit to manage the flows of people and refuse. Epidemiological studies linked environmental conditions to outbreaks, leading to sanitary reforms and the professionalization of public health. Yet improvements were incremental and frequently prioritized central districts over poorer neighborhoods.

– Sewage and clean water reduced some waterborne illnesses over time.

– Public transit reshaped commuting and suburban growth patterns.

Infrastructure projects required capital and political will, often catalyzing debates about taxation and urban governance. The resulting networks set patterns for modern city management.

Cultural and social networks

Urban concentration fostered new cultural forms and social institutions, from newspapers and theaters to clubs and educational societies. Shared public spaces such as markets, parks, and transportation hubs became arenas of daily interaction and cultural exchange. Immigrant and migrant communities developed institutions that preserved traditions while adapting to city life, contributing to a plurality of urban cultures. These networks provided identity, support, and channels for civic participation.

Leisure industries and voluntary associations also expanded, offering both diversion and platforms for reform. The city’s cultural vibrancy was a key factor in its appeal.

Conclusion

Urban growth in the nineteenth century was a decisive force that reshaped social and material life.

It created challenges that spurred institutional innovation in housing, health, and labor.

Those responses established institutional templates that influence cities today.