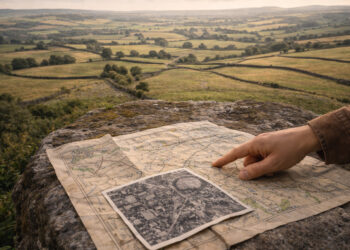

Human communities leave traces on the land that outlast political maps and written records. These environmental clues—field boundaries, soil changes, waterworks, and vegetation patterns—help reconstruct how regions were organized and used over long periods. Reading these traces requires combining landscape reading with documentary and archaeological evidence to build coherent regional narratives. This introduction outlines how geographies of past regions can be rediscovered through careful observation and interpretation.

The material record in the landscape

The first step in regional reconstruction is cataloguing visible material features and their spatial relationships. Old hedgerows, terraces, abandoned settlements, and relict roadways form a distributed archive that records economic choices, labor investment, and settlement hierarchies. Interpreting these features involves dating, mapping, and considering how later activities may have altered or obscured earlier patterns. Together they provide a baseline for questions about continuity and change across a region.

Human mobility and settlement patterns

Patterns of habitation and movement shape how landscapes look and how regions functioned. Settlement density, nucleation versus dispersed farms, and proximity to trade routes all leave detectable marks on land use and resource distribution. These traces indicate social organization, property regimes, and connections between communities.

– Settlement clusters often align with water access and arable land.

– Pathways and trackways reveal long-distance movement and economic exchange.

– Temporary camps and seasonal use areas show adaptive strategies.

A combined view of mobility and settlement helps explain why some places persisted as centers while others declined, and suggests how networks knitted a region together.

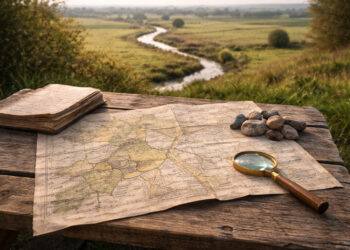

Natural features as persistent markers

Rivers, ridgelines, wetlands, and soil types provide durable templates that mediate human choice and institutional boundaries. While political borders can shift, natural features often constrain economic possibilities and settlement locations across centuries. Vegetation patterns and floodplain dynamics, for example, indicate former land management and can reveal earlier agricultural regimes. Recognizing these persistent markers anchors historical interpretation to ecological realities.

Methods for interpreting regional evidence

Effective regional analysis blends field survey, remote sensing, archival research, and community knowledge. GIS mapping synthesizes these datasets to reveal spatial patterns that are not obvious at ground level. Comparative study—looking across similar environments or neighboring regions—tests hypotheses about drivers of change and persistence. These methods make it possible to turn dispersed traces into plausible stories about past regional organization.

Conclusion

Environmental clues provide a resilient record of how regions were formed, used, and reorganized over time. Integrating landscape evidence with documentary and archaeological methods produces richer, place-based histories. Such approaches help recover regional identities and processes that written sources alone often obscure.