Regions are not fixed containers drawn on a map but living assemblages shaped by geology, climate, and human action. Over generations, rivers, roads, and trade routes stitch together economies and cultures, while natural features channel settlement and memory. Local practices and infrastructures respond to opportunity and constraint, producing durable patterns that scholars call regional character. Recognizing this complexity helps planners, teachers, and citizens engage with place in more informed ways.

Geography and Material Foundations

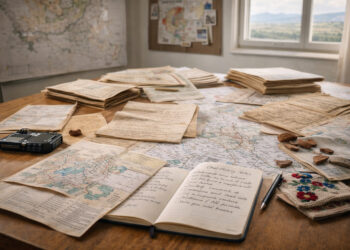

Physical landscapes set the stage for many regional differences by influencing where people live, what they grow, and how they move. Mountains and coasts create both barriers and gateways; soils and water availability shape agricultural choices and settlement density. Infrastructure such as roads, ports, and canals then amplifies or redirects these initial advantages, knitting smaller communities into broader economic systems. Over time, material conditions generate visible legacies in town patterns, land use, and built heritage.

These material foundations do not determine outcomes alone but constrain and enable social choices. Reading them offers a tangible route into a region’s past.

Movements of People and Goods

Migration, trade, and labor flows are primary engines of regional change, introducing new skills, beliefs, and economic links. Markets and migration corridors can transform marginal zones into hubs, altering demographic balances and cultural practices. Seasonal labor and long-distance trade create layered ties that extend local identities beyond administrative lines. Because such movements are uneven, they also produce internal inequalities and cultural mosaics within regions.

Tracking these flows clarifies how regions adapt to disruption and opportunity. It also highlights the ephemeral networks that nonetheless leave lasting marks.

Stories, Institutions, and Memory

Institutions—municipal governments, religious bodies, schools—mediate how communities organize space and resources, shaping civic habits and expectations. Public narratives, commemorations, and local histories craft meanings that bind people to place, often simplifying complex pasts into shared symbols. Museums, archives, and festivals selectively preserve elements of regional identity while silencing others; this curation affects which stories endure. Together, institutional practice and collective memory sustain a sense of belonging that outlives individual lifespans.

Understanding these cultural mechanisms reveals why some identities persist through change while others fade. Engaging critically with memory can open more inclusive regional narratives.

Conclusion

Regions emerge from the interplay of environment, movement, and meaning.

They are built by decisions, networks, and stories that accumulate across generations.

Seeing this process encourages thoughtful stewardship and richer public conversations.